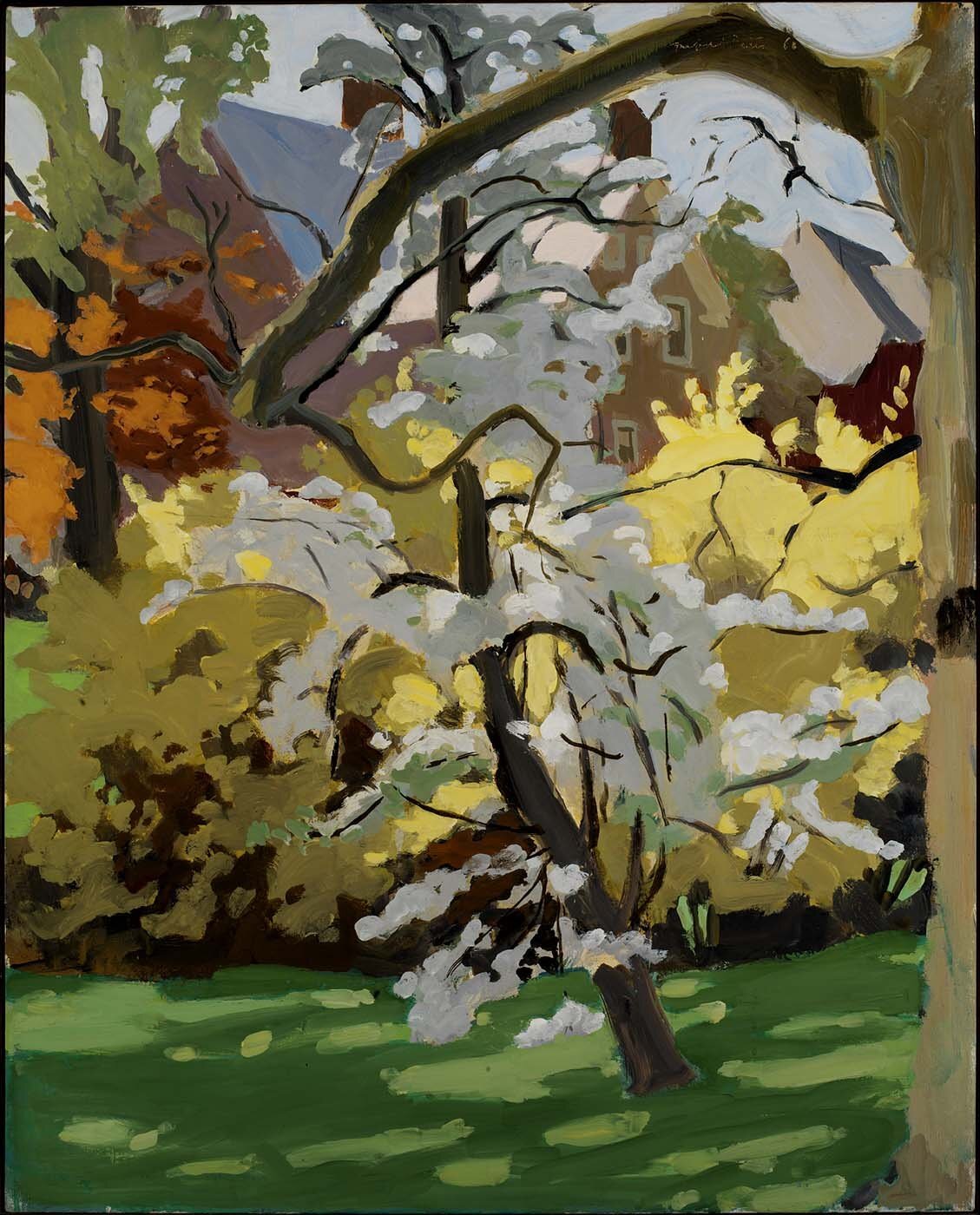

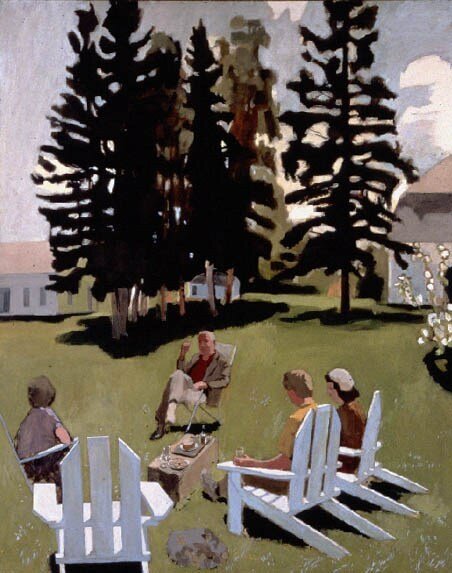

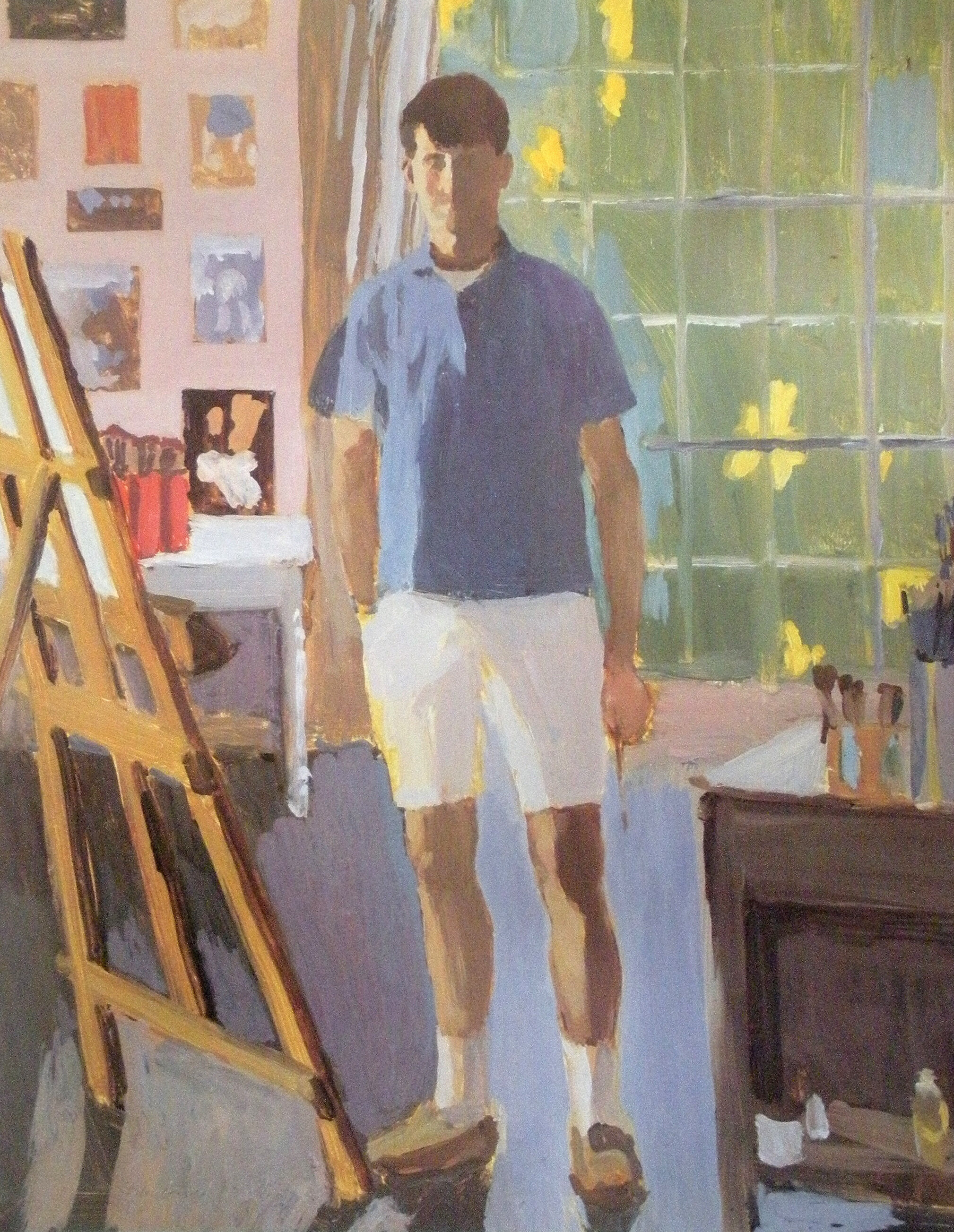

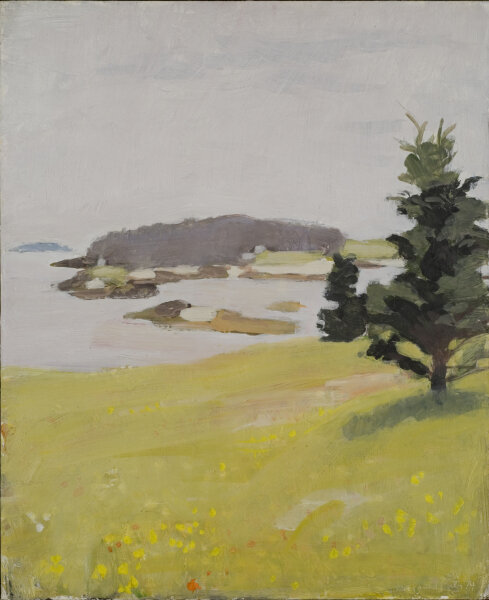

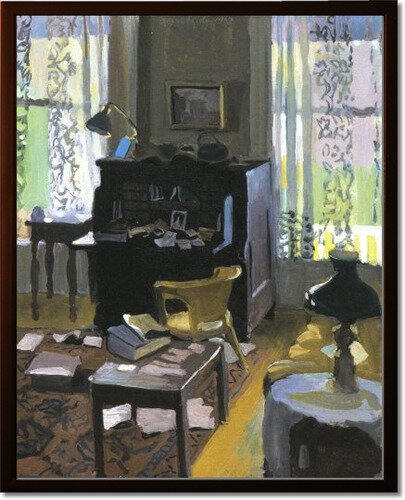

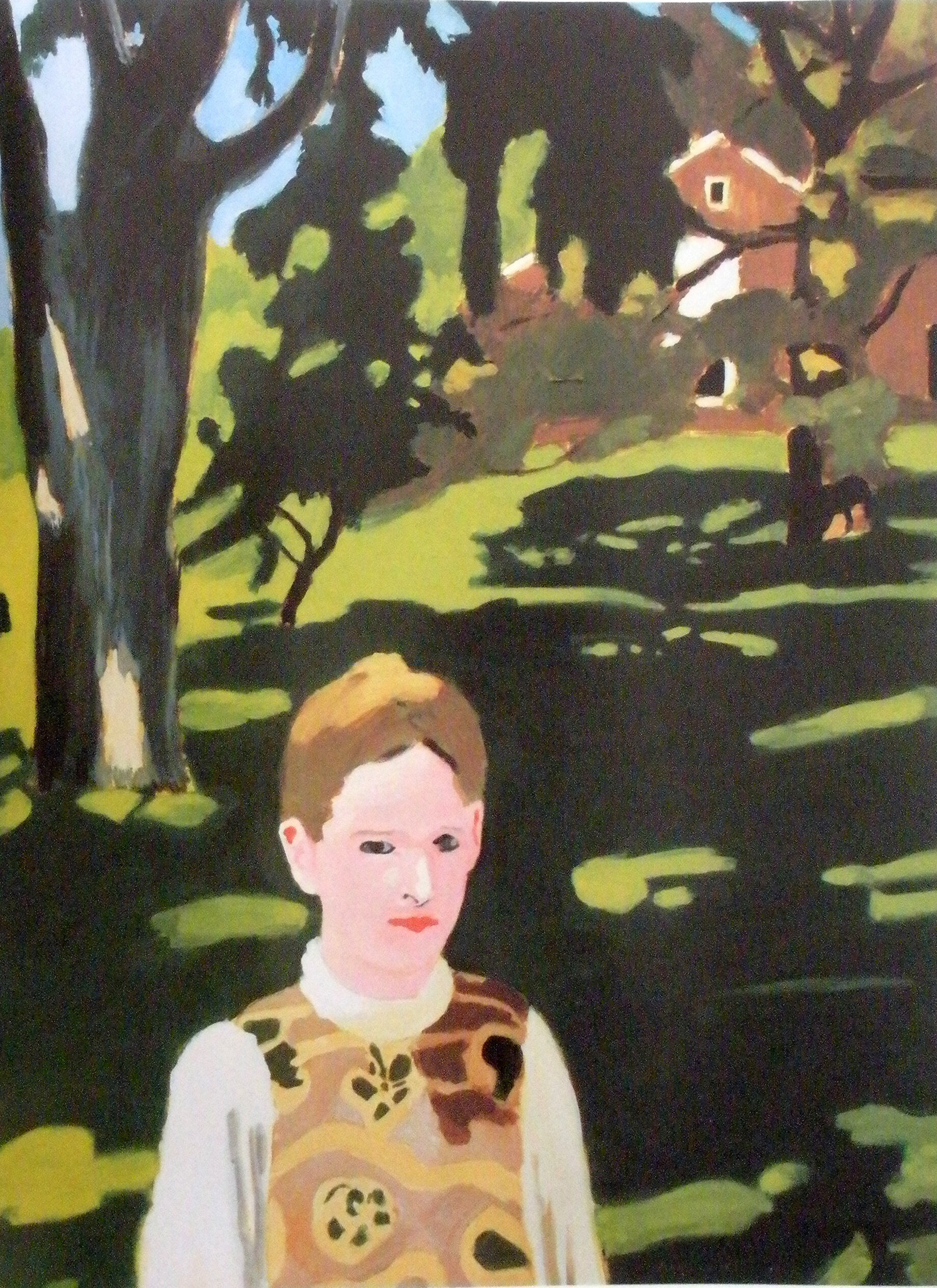

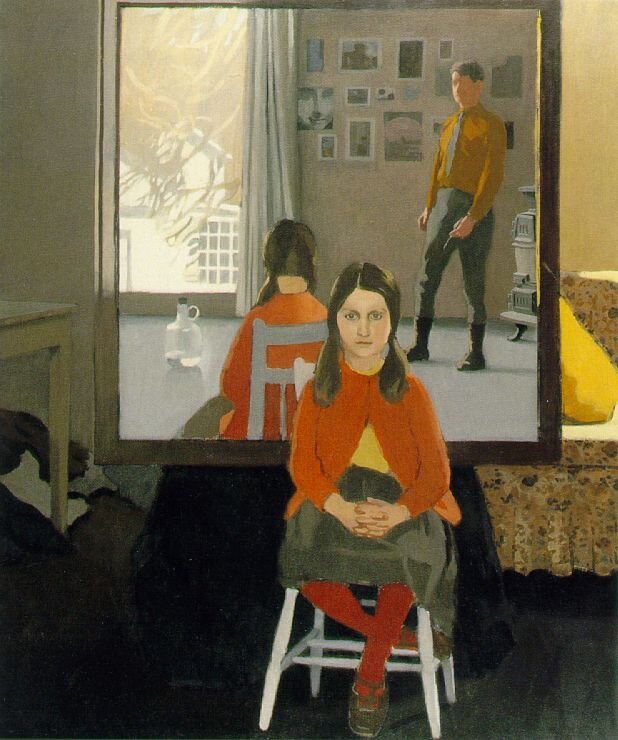

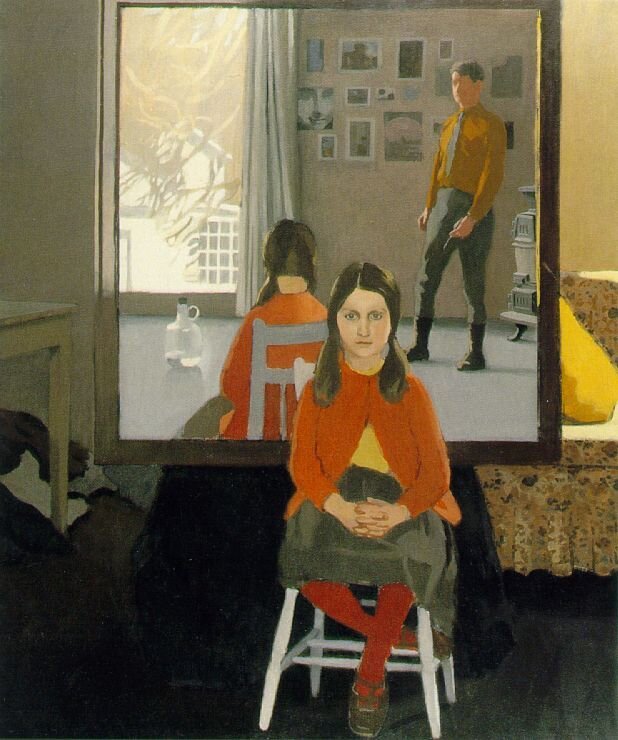

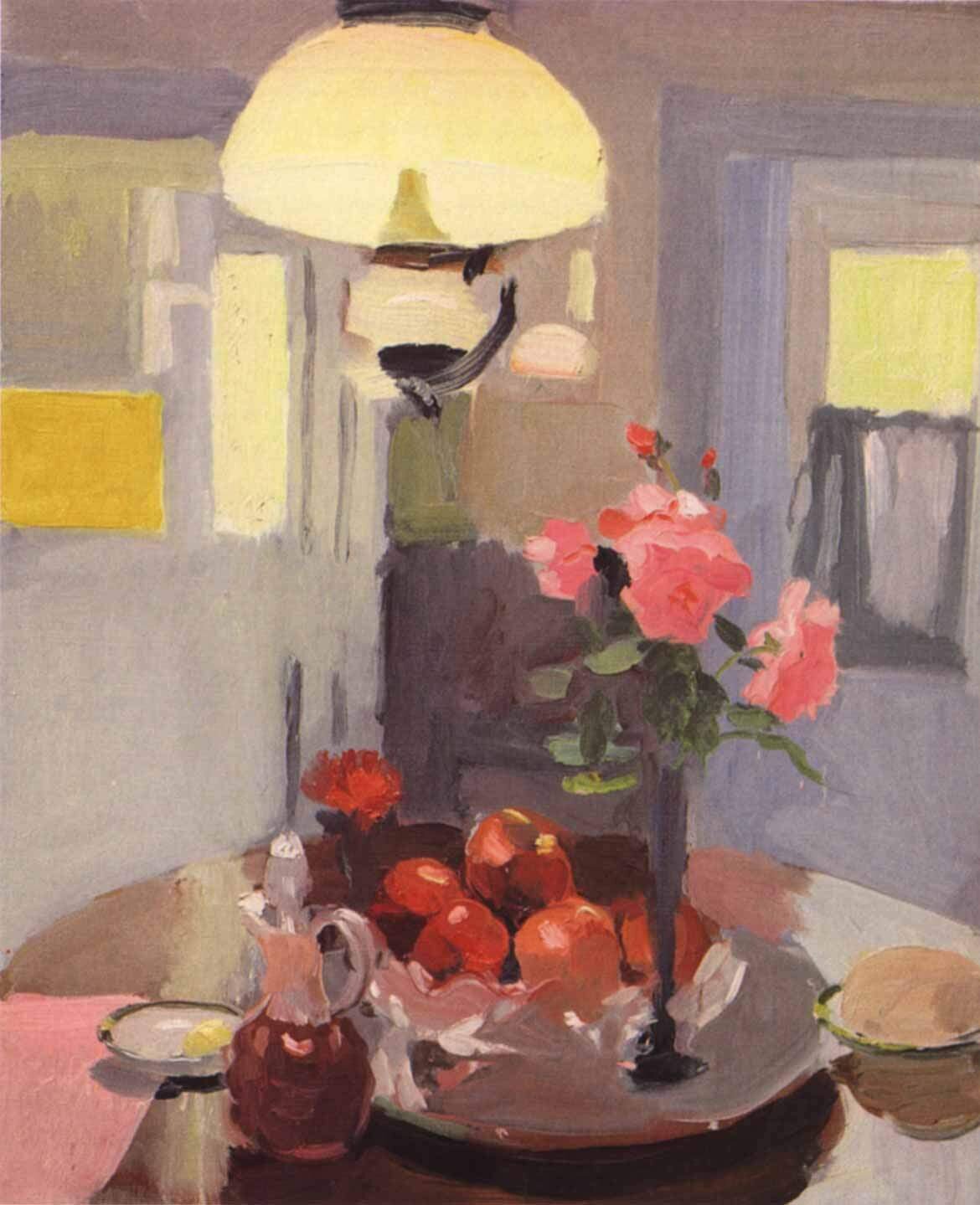

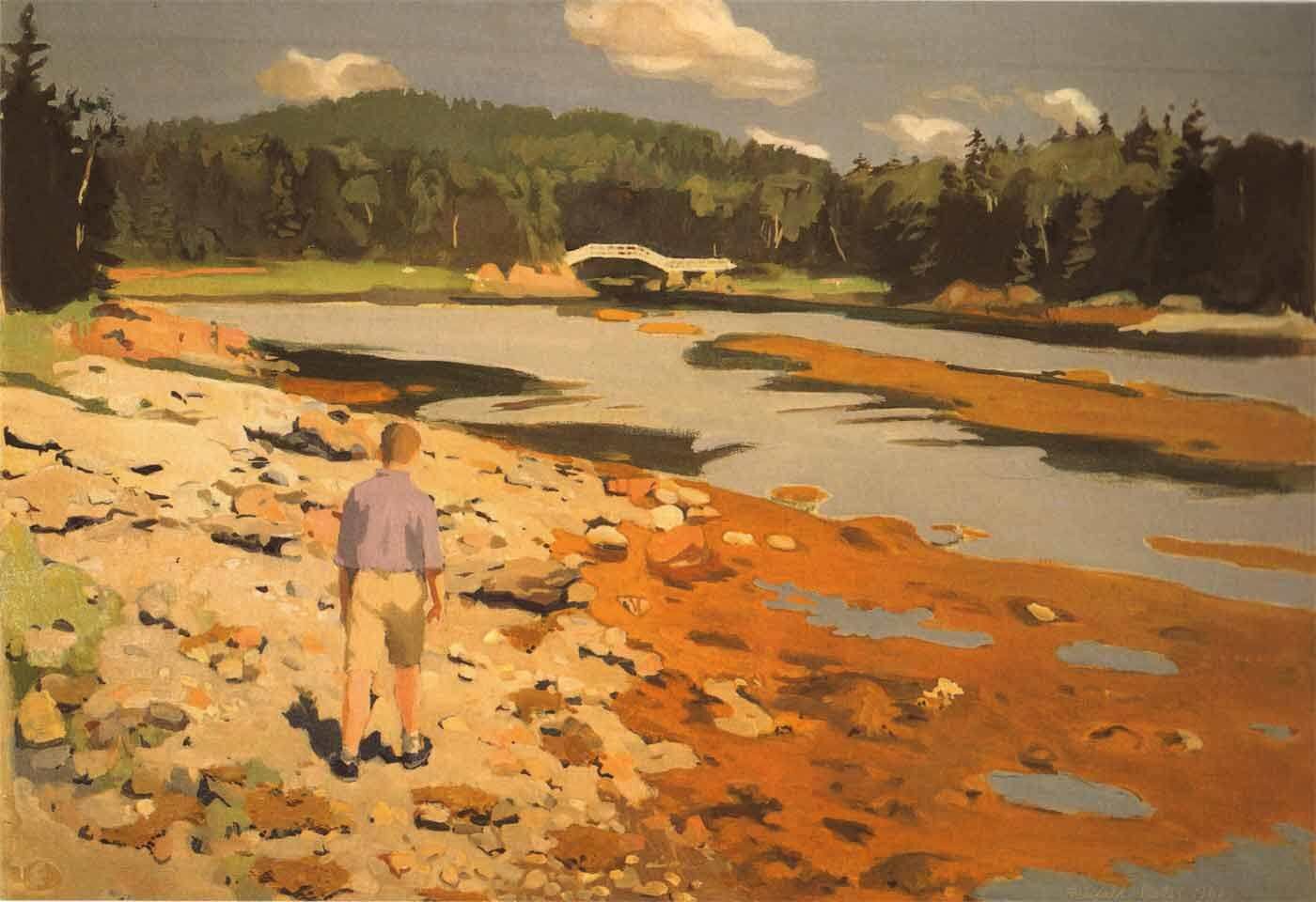

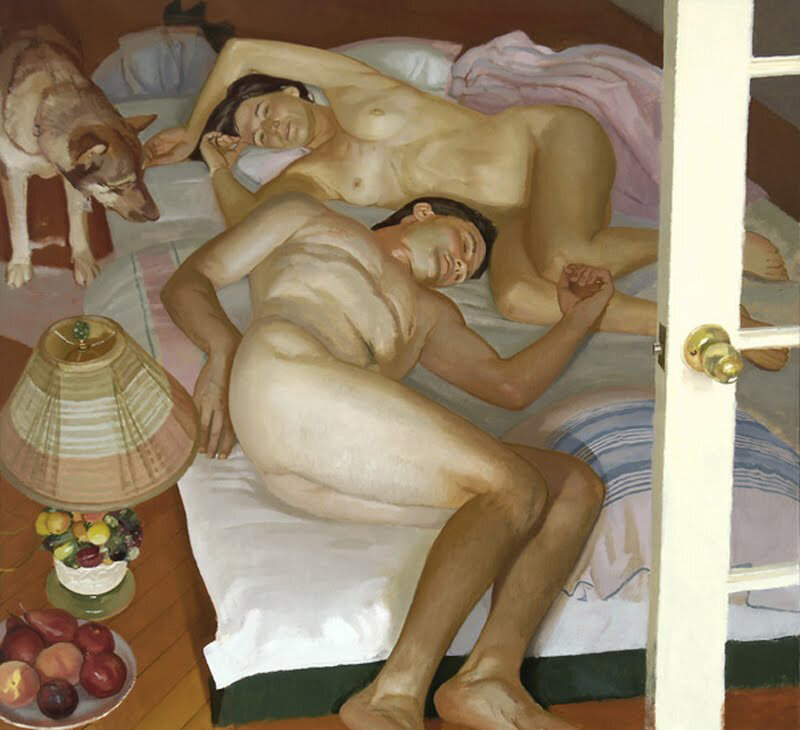

Every once in a while I think, "painting is so difficult." Truthfully it is. It is work to see beauty in everything and even more to be capable of expressing it in paint. It takes a keen mind and a passionate heart far beyond the rigors of technique alone. It seems to me that every time Fairfield Porter put brush to canvas it was with a precise intention and the sheer joy of being alive and looking at life. His paintings continue to inspire me to look here and now. To be not only present, but to search for beauty in my immediate surroundings.

There has been so much written about and by Porter in addition to his paintings, which speak volumes. I came across this interview in which "Porter speaks of his family background and Harvard education; the Art Students League; his involvement with Marxism and his work as an art critic for ART NEWS and THE NATION. He discusses his portrait commissions, his choice of subject matter, theories of realism versus abstraction and drawing versus color, and the role of the unconscious and the accidental in his art. He recalls Thomas Hart Benton, Jacques Maroger, Elaine and Willem de Kooning, Walter Auerbach, Thomas B. Hess, Clement Greenberg, and Alex Katz." (Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.) I thought I would share it with you.

In addition to this interview there are many other readings and resources to be found online. There is a fantastic blog post about Porter with many links and quotes on Painting Perceptions.

I have included additional links after the article including the original source. I hope you enjoy!

Interview with Fairfield Porter

Conducted by Paul Cummings

In Southampton, New York

June 6, 1968

Biographical/Historical Note: Fairfield Porter (1907-1975) was a painter and critic from Southampton, N.Y.

The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Fairfield Porter on June 6, 1968. The interview took place in Southampton, New York, and was conducted by Paul Cummings for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

This interview is part of the Archives of American Art Oral History Program, started in 1958 to document the history of the visual arts in the United States, primarily through interviews with artists, historians, dealers, critics and others.

Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service.

Interview

PAUL CUMMINGS: It's June 6 and Paul Cummings talking to Fairfield Porter in beautiful Southampton. You were born in Winnetka?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Winnetka, Illinois, June 10, 1907.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Tell me about living there. Do you come from a large family? Small family?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Five children. One sister, who is the oldest. Next is my brother Elliott, who is the photographer, a very famous photographer. Then another brother, then me, and then the younger brother.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Are they all involved in the arts?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: No. Only Elliott in photography. But he's an M.D. He taught bacteriology and endocrinology at Harvard Medical School but never practiced medicine. Then he gave it all up for photography, which he had done since he was a little boy--taking bird pictures, you know, hiding in blinds and taking pictures of birds opposite their nests. So that really his first interest was photography.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Your parents must have decided you all needed good educations, because you went to Harvard.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes.

PAUL CUMMINGS: What kind of place was Winnetka to live in then? Did you live there till you went away to college?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes. We went to Maine in the summers. Winnetka is a wealthy suburb of Chicago. It s like Scarsdale or Bryn Mawr.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Well, did you go into Chicago?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes. I remember being taken to the Art Institute by my mother, and I remember the first paintings that.... I remember I always liked to see paintings, and the paintings that I can remember in the Art Institute are Giovanni di Paolo. I think it was because it had the Beheading of St. John the Baptist in it, which was sort of fascinatingly gory.

PAUL CUMMINGS: That appealed to youth.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: When I was twelve ... And Rockwell Kent I liked very much. Then I remember, when I was about twelve or thirteen, an exhibition of Picasso, that Egyptian period, those great big heads. That impressed me very much. I thought, if this is what painting is today, it's a significant activity.

PAUL CUMMINGS: This must have been around 1920 or so.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Was that your first adventure into the museum?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Well, I was always good at art in public school which we went to.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Did you do drawings when you were very young?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes. I copied Howard Pyle and I copied photographs. I remember once in art class in grammar school. Everybody was supposed to bring a flower to school and paint it, and I didn't bring anything. So they gave me a piece of timothy grass. I had a brush that was crooked; it was bent. And the teacher liked my rendering of timothy grass better than anybody else's thing. She held it up before the class and said: Look what he did, and with that terrible brush.

PAUL CUMMINGS: That's interesting. That was when?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: That was in grammar school.

PAUL CUMMINGS: What kind of schools did you go to?

PAUL CUMMINGS: They were very good public schools. Since then, since my time, the Winnetka public school system has become one of the best in the country. In my time, it was good; that's all– good, ordinary public school.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: What kind of family background did you have?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: My father was an architect. He built the house in which we lived. I still think it's one of the most beautiful Greek revival houses in the United States. I like it better or just as well as anything I've seen in Virginia, which is a little earlier, of course, not Greek Revival. But he didn't remain interested in architecture.

PAUL CUMMINGS: So what did he do?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: He just looked after his own affairs and his own real estate in Chicago.

PAUL CUMMINGS: So you had a very comfortable family life.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Very comfortable. Yes.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Were you involved with your brothers and sister very much?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Oh, certainly. Yes, very much.

PAUL CUMMINGS: I know some of the people I've talked to have been very insular because of their art interest, and the other children didn't understand it much.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: No. My art interest wasn't that decisive or active, and anyway it wouldn't have isolated me.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Well, if you lived in a house like this in an area... You didn't play the same kind of games that apartment dwelling children play.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: No.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Did you have a lot of friends in school?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: No. I was rather isolated at school except the first school I went to - which was a private school- when I was five and was there for about three years. Then I went to public school, and public school sort of frightened me partly because I was a good deal younger than the other kinds in my own grade. I was two years younger. I wasn't very athletic but neither were my brothers. We were all like that, but they didn't have the disadvantage of being a couple of years younger than their group.

PAUL CUMMINGS: It makes a lot of difference.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Oh, yes, it does. I realize that. It's very important.

PAUL CUMMINGS: What was the prep school that you went to?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I went to Milton Academy for a while, but that was just to.... I had already been admitted to Harvard. That was just to hold me back a year. I didn't finish the year at Milton. I came home to my sister's wedding and didn't go back to school.

PAUL CUMMINGS: So you must have gone to Harvard very young then.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I was 17 in my freshman year.

PAUL CUMMINGS: What did you study there?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I majored in fine arts but just barely. I got an S.B. degree, which meant that I didn't take the Latin requirements which they wanted then for an A.B. degree.

PAUL CUMMINGS: What's an S.B.?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Bachelor of Science in the fine arts.

PAUL CUMMINGS: How did they figure that?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: It only meant the Latin requirement has not been passes. That's all it meant. It was an inferior degree to an A.B. In a certain sense.

PAUL CUMMINGS: I see. Well let's not really get into college yet. Did you do a lot of reading in childhood? Did you have books around?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I read H.G. Wells science fiction. That's what I remember. I remember mother used to read a great deal to us, Dickens. What I read to myself was H.G. Wells, The First Man in the Moon and everything that I could get by him.

PAUL CUMMINGS: He's very exciting. I read a lot of him, too, at one time.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I think because of H.G. Wells, my brother Edward, older then I, and I and two neighboring girls spent a lot of time making up a country in Mars; and we drew maps of it and discussed its sociology and that sort of stuff. This all came from H.G. Wells.

PAUL CUMMINGS: So you really built a whole world. That's great. Were you interested in music?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: No. I'm not particularly musical. The family isn't either. There was a player organ in the house which father played. There were certain things that I got very familiar with and liked very much. I like music when it's easy for me to pay attention.

PAUL CUMMINGS: You didn't have any languages at home, did you?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: German. We had a German governess. I knew German very well. The last time I went to Germany which is a long time ago, I found that German came back to me very, very fast. I was mostly in Italy; that was 1932. I went to Germany and I came back to Italy. I had picked up Italian, so I could play bridge with the people in the pension. There was an Austrian woman in the pension; and she said: You speak German better than Italian.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Were languages easy for you?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I don t know if it was easy for me or not. I think that an ability for language goes along with an ability for math, which I never had. I I've never tested it, so I don t know whether languages are easy for me.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Well, you learned Italian.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I learned Italian when I went there. Yes. And I learned it in a few months. I read the newspapers and I talked to people, but it was a very limited knowledge.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Do you read German?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I don t read any foreign language now except French with great difficulty. I mean, that s the easiest for me to read. I can t read German any more.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Do you think you could pick it up if you went to Germany?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I might, yes. The pronunciation is easy for me.

PAUL CUMMINGS: How did you get a German governess?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Well, this was before the First World War, and German was the prestigious foreign language for people to learn. That was stopped as the result of the First World War. I think the chief influences on me as a child were my father s interest in art and architecture. We had photographs all over the house of great Italian paintings and of architecture. He used to talk to us about how Gothic architecture was organic and how Greek architecture was organic, too. I don t really understand that. I now think that Greek architecture perhaps you couldn't say was organic. But he didn't understand the Renaissance at all. He didn't like it.

When I was fourteen, we were in London. We went on a Mediterranean cruise, and we went to London. I remember in the National Gallery going to see the Leonardo Virgin of the Rocks, which I liked very much because it was familiar to me from photographs. I discovered something which I didn t know from photographs at home; and that was Titian, The Rape of Europa and Veronese's The Family of Darius Before Alexander and Turner. These were my own discoveries. Nobody told me anything about them except they were names, of course.

PAUL CUMMINGS: But you didn't see reproductions?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: No. Nobody said these are great. My father didn't say these are good nor did anybody else. My father liked Leonardo and Michelangelo.

PAUL CUMMINGS: But you really discovered the Renaissance on your own in a

way.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes. And when I studied art at Harvard and I came home--we lived for a while at my grandmother s house after she died-I realized that what was art history for my father began where with my education it had stopped. The primitive was Leonardo, and for me he was almost the very end except the Venetian painters. The early Venetian painters, my father didn't consider. It was the 17th century Italian painters--the Mannerists, the Roman School, and so on--that he thought were the great names. And I hardly knew who they were. But he didn't know anything about Giotto or Piero or the 14th and 15th century painters.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Just that one block of time. That s very strange. Well, did you have paintings around the house?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Just photographs. And you know those casts made in Boston-I don t know if they still sell them there--of the Parthenon frieze? We had maybe ten of them around the house. So I got very familiar with fifth century Greek sculpture, you know, from just that. And then I remember father once.... The casts got sort of dusty. They were of plaster, and he got sort of tired of this texture. So he painted them with a green copper paint and then rubbed shoe blacking on top. They looked as though they d been made of bronze with patina and hollows and so on. I liked that very much.

PAUL CUMMINGS: It was a great transition from pure white to patina bronze. Well, did you ever have an interest in being an architect because of his influence?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes, I did. I think I took some private lessons in painting, when I came home in the spring from Milton Academy to my sister s wedding, to give me something to do. Then when I went to Harvard, I took a beginning course--the course open to freshmen in fine arts which was called Drawing and Painting and Principles of Design. The teacher was Arthur Pope. I learned a tremendous amount from him. I remember telling my tutor that I liked his course as well as any in fine arts. He said: Well, there can by only one awakening. Pope wasn't a particularly popular lecturer. He kind of mumbled, and people went to sleep in the class. But I was interested in what he was saying so I heard everything.

PAUL CUMMINGS: How long did you have him? For one year?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: For one year only. After that, I took historical courses.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Did you take painting courses at Harvard?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: They didn't have any. They had a very few but they weren't.... I was more interested in the historical ones.

PAUL CUMMINGS: So you really have a solid background as an art historian?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Well, superficial.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Well, I mean, you know, who knows? I'm interested in your discovery of Titian.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I think it was the color.

PAUL CUMMINGS: How old were you when that happened?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: About 14, I think. I was 13 or 14, 14 I think.

PAUL CUMMINGS: That was your first trip to Europe, was it?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes, around the Mediterranean, a Mediterranean cruise.

PAUL CUMMINGS: How did you like that?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Oh, very, very, very much.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Have you don't it again?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Last summer I took the two little girls and my wife to Italy. But, no, we went through; we took the Italian Line. The ship stopped at Gibraltar. We passed the Azores. The Azores were the first foreign land that I saw. The ship stopped; it was a cruise ship. We walked around Ponta Delgada, which is the capital, I believe. That seemed to me just incredibly beautiful– these Mediterranean plaster houses painted like the colors of a Parcheesi game.

PAUL CUMMINGS: And the light was so different there from where you'd been before.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes. The Azores... Sometimes I think I'd like to go and stay for a while and paint. We passed by last summer very close to it, to another island, Santa Cruz; and it's very wet apparently. Its; not like Ireland. I mean there's plenty of water, because there are waterfalls falling off the cliffs all around. Then there are these little villages and little Portuguese churches, white with black stripes. It's all sort of a lump, Santa Cruz is.

PAUL CUMMINGS: What kind of family background do you have? It wasn't German. Is it English?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Its English. My parents were born in the middle west. My father was born in Racine, Wisconsin. My mother was born in Chicago. My father's mother was born in Chicago on a farm at something like Randolph and Wabash Avenues, which is where the family money comes from. They had the good fortune to have been born on a farm that turned out to be the Loop later on.

PAUL CUMMINGS: That's pretty great. So really, they've been here for quite a while.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes, from the 17th century. I think I have ancestors who came over on the Mayflower. I'm not sure but I think I do.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Oh that's entrenched American. When do you really think your interest in art started? When you were an early teenager? Earlier?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Well, children, you know, like to draw. That doesn't prove anything, but I sort of stuck with it for some reason. I don't know why. I think I might have had literary interests except that, for some reason, I read very slowly. I managed to do very well in school in spite of that. I'm what they would call nowadays a reading problem. Although it didn't especially show except that it comes out in that I Read at about half the speed of a normal person. It's probably the thing that there's so much of nowadays. Its so noticeable nowadays when they try to teach people to read a sentence at a time. They never learn the words. But I was taught the old-fashioned way, to spell out each syllable.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Well, do you think the art interest then was communication or escape or a kind of focal point?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I was just always very interested in looking at paintings.

PAUL CUMMINGS: It was a visual like.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Was there anyone that influenced you to continue when you were young, or was it your won motivation would you say?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: No, I don't think anybody influenced me to continue, but being a painter was somehow related to my father'... my father really didn't present any example of an abiding interest which was his work. He was interested in architecture and the arts, but he didn't do anything about it anymore except... He had given up his architecture.

I have a feeling though about his architecture, you know, modern architecture when it came along, Frank Lloyd Wright and so on... I have a feeling that he understood something that modern architects don't- which is the plan. Modern architects, you know... there's a great deal of feeling, or there used to be, that classical ornament is old- fashioned. So they sort of concentrate on- or they did for a long time- the look of a building. And they said a classical building... My father's house they would have said was a monument, not a functional building. But as a matter of fact, it's very, very much more functional; because it's more practical. The difference between a modern architectured house and what my father made was simply that they gave up the look of the classical monument and decided to make something that had the look of something else. But they don't go any farther than just how it looks on the outside. It's just a change in fashion, and they're not the least bit more functional than anybody else. You constantly hear stories about that, you know. A house is a machine for living; Corbusier likes this phrase. But you see a house by Corbusier, and it always leaks. The rain comes through the roof. He doesn't keep out the weather.

PAUL CUMMINGS: It's not a functional house; it's a building.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes. It's an amusing and tricky thing.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Yes. That's true. Many people I know who live in modern homes find them extraordinarily difficult. They're too removed from...

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes. What happens is that instead of using conventional, classical ornamentation, they use something completely whimsical and personal, which might be better but hardly ever is.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Well, what kind of buildings did you father do? Did he do homes?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Homes and a railroad station or two. That's all. He was a domestic architect.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Well, let's get back to Harvard a little more. You spent what, four years there and you got the degree?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes. Then I went to Art Students League.

PAUL CUMMINGS: And you studied with Robinson and Benton?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Well, before we go to the League, how would you evaluate the art education you got at Harvard?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I think it was very good. I don't think I could have gotten a better education anywhere else at that time just as far as history and so on is concerned, in aesthetics it was weak, but weakness came from the fact that there wasn't any relation to practice.

PAUL CUMMINGS: It was all theory?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: It was theory, and the theory didn't go very deep. It was superficial theory, and I found that our much, much later when I met de Kooning. First I thought I found it out when I studied with Benton. He seemed to go further. But then when I met de Kooning, I thought Benton, too, was not too deep. It didn't, with him, come enough out of practice. It came a little too much out of the idea comes first and you apply it.

PAUL CUMMINGS: So it was illustration in the sense of...

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Well, yes. Sometimes the illustration is very good in a person who is like that. They do it very well.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Well, what kind of theory did you find or did your acquire at Harvard?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Well, they would say, "Here's the surface of the painting" and "This is well composed." Composition is the most important thing, and composition means that they analyzed it. I think Professor Pope did too. Repetition and sequence and probably another thing, I don't know what, harmony maybe. I found out many, many years later that composition isn't good because something is repeated but because it is not repeated. It was just the opposite. If there's something that never occurs again in painting, that's what...

PAUL CUMMINGS: Its unique quality is what makes it work.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Let's see, you were at Harvard in about the early 20s?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I graduated in 1928, 1924 to 1928.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Was there anyone there interested in modern art at that point?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes, Pope was interested in modern art. He explained Cubism to us in an interesting way. Analytical Cubism he said was like jazz, which I think is true. That's an intuitive remark, but I think is true. Analytical Cubism he said was like jazz, which I think is true. That's an intuitive remark but I think it's true. Also we were presented with the aesthetic theories of Berenson, and that was a very strong influence on me. I think that I can't even today look at Florentine painting without doing it in Berenson's terms.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Has it maintained itself as an influence or has it changed?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: What?

PAUL CUMMINGS: Well, Berenson's aesthetics applied elsewhere.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I don't know about them applied elsewhere. I met him when I was in Italy in 1932, and I remember telling him that I liked Tintoretto and Rubens because I'd learned to like them from Thomas Benton. And he said: Yes, I know what you mean about them, but the best painter of all is really Veronese or Velazquez. At that times I didn't like either Velazquez better than any other painter now.

PAUL CUMMINGS: When did you make that discovery or decision?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I think when I saw the Velazquez after the last war. There was a show of the paintings of the Kaiser Friedrich Museum in The Metropolitan, and there were some Velazquez Infantas. I'd seen then before in Berlin. But I saw them again, and I was struck by the... I was interested, I think... I was beginning to be interested in what you can do with paint, what is the quality of paint, what is its nature. And this liquid surface of Velazquez, I admired and also what might be called understatement. Although I don't like that word really. The impersonality... I don't know what word to use. He leaves things alone, you know. It isn't that he copies nature, but he doesn't impose himself upon it. He is open to it rather than wanting to twist it.

PAUL CUMMINGS: In other words, he will let it dictate to him.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes. I think there is more there, you know. Let the paint dictate t you or let yourself be dictated to. I think there's more there then there is in willful manipulation. It's like I used to like Dostoevski very, very , very much. No w I prefer Tolstoy for the same reason. He is like Velazquez for me.

PAUL CUMMINGS: You just let that happen.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes. And he knows what... He's open and he also knows when it's unimportant to pay attention. Or Chekhov. I mean Chekhov and Tolstoy have that quality of not being on top but being "with it" as people say nowadays.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Yes, I see what you mean. Well, was there anyone besides Pope at Harvard who you feel was influential?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Porter (who is no relation) in fine arts. I took a very interesting course with him on pre-Romanesque.

PAUL CUMMINGS: What's his full name?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Arthur Kingsley Porter, pre-Romanesque art. It wasn't a set course. He didn't know everything yet. It was as he was discovering things he gave them to us. We were sort of watching his research. And I took a course with Whitehead in philosophy that was very, very interesting. And Langer in history. He's the ex-husband of Susanne Langer, the aesthetician. I was very interested in his course on 19th- century European History.

PAUL CUMMINGS: What was Whitehead like as an instructor?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: My wife also studied with Whitehead at Bryn Mawr and at Radcliffe. He didn't expect that his students would understand everything, but he want in any way patronizing,. Although he sort of treated us like very small children. He also thought that the whole subject of philosophy was really very simple. I remember his examinations would consist of twelve questions, and he would say write on any four. You'd look over these twelve questions; and you'd realize that, if you answered any one of them, you'd tell the whole course.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Do you remember what kind of questions he would ask?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Well, what I remember of what I got from him- I got it a little later when I read a little bit of him and I also got it at the time- was the importance of having very clear terms in your discussion and knowing what they mean. In other words, he wanted to escape from vagueness. For instance, he drew a diagram on the blackboard, a circle, an irregular enclosed curve, and then another irregular enclosed curve, and then another irregular enclosed curve which maybe he slapped over it; and he called one A and the other B. And then he said that A has the relationship of extensive connection with B . And he said: To escape from poetry of the phrase, the relationship of extensive connection, I will call that phrase R. So A, R, B. Then he said you don't use synonyms; you don't write good English in the sense of never repeating yourself. If you are sure of your terms, you repeat yourself; because he knew what he wanted to say. So he used.... That was the word: "to use." He "used" it again.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Over and over and over so it really made its point.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes. Then I realized again reading him that, even if you used symbols, you can't get away from poetry. Because if you say A, R, B, somehow it's a little different from saying B, R, A.

PAUL CUMMINGS: That's right.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: H pointed that out. So, I mean, it's impossible perhaps. He also told us that the.... This relates I think, to what I'm interested in painting, too, in aesthetics. That's why I mention it. But he taught us that Hume's criticism was practically unanswerable, you know. What do you know? And Hume's idea that all you know is one sensation after another; you do not know the connections between them. That was what he was concerned with doing, finding an answer to Hume who he thought had not been adequately answered by Kant, I guess. And he thought he did have an answer, but still, you know, it's... And I think, therefore, what I like in painting; because it seems to me to relate to that. I mean, I like in art when the artist doesn't know what he knows in general; he only knows what he knows specifically. And what he knows in general or what can be known in general becomes apparent later on by what he has had to put down. That is to me the most interesting art form. It expresses that. In other words you are not in control of nature quite; you are part of nature. It doesn't mean that you are helpless either. It just means that the whole question in art is to be wide awake, to be as attentive as possible for the artist and for the person who looks at it or listens to it. That, of course, comes out in people's fondness for drugs nowadays. I've never taken any, but what it apparently gives hem is it enables them. It just gives them the ability to be attentive as they never have been before. I've talked to people who admit it, and that's what comes out.

PAUL CUMMINGS: It clarifies.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes.

PAUL CUMMINGS: That's interesting. I hadn't actually heard that from any of the people I know who use drugs. They've all had different kinds of experiences.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Well, I'm interpreting what I've heard. One of the persons who's use drugs wouldn't have told me just that. I sort of led it around that way. But he's a painter too, and he doesn't use them any more. Then from what I've read, for instance, Alan Watts and so on... When he takes drugs and when he doesn't close his eyes and have a vision... But when he looks at what's there, he sees what is revealed to him is what anybody could tell you is there without taking drugs. Only it comes as a revelation.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Because he just doesn't normally see it?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Well, he isn't attentive enough.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Yes. Do you still read a great deal?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Is there any particular area of literature that intrigues you more than others?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I don't know. I can't say.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Do you read things like history and novels and all that sort of thing?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Not terribly much. I don't like most modern novels very much. I just can't get into them. I can't get interested. I do like Tolstoy very much. I read some Tolstoy recently; just thins year I've been reading the things I haven't yet read, short things.

PAUL CUMMINGS: So Harvard was really rewarding for you?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Did you meet any people who became long- term friends or students who were important to you?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: No I didn't. I haven't maintained those friendships that I had. I was again rather isolated there. I didn't really much meet people on a basis of easy give-and-take until I went to the Art Students League.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Oh, really? Why was that, do you think?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Well, because they were... I didn't feel I had any apologies to make for myself.

PAUL CUMMINGS: You were also very independent it seems. Well, what about the League? How did you pick the League after having gone to Harvard?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I had some friends in New York, one of whom became my sister-in-law, who had gone to the League. I used to come down to New York once in a while from college. They were going to the League, and that's what decided me to go there. I like its setup; it didn't seem to me to be academic. And, of course, it's run by the students. They chose artists whom they admired to come and teach id they would. And the artists, the people who were teaching there – people like Boardman Robinson, Thomas Benton - were people who I respected more than teachers who were simply teachers in other schools.

PAUL CUMMINGS: How long were you there?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Two years.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Did you work with anyone else besides Robinson and Benton?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes.

PAUL CUMMINGS: How did you like them as teachers?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I liked Robinson best, because he was a teacher. He taught you; he didn't teach a system. He taught the person he was talking to.

PAUL CUMMINGS: So it would change with the students?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes. He didn't seem to ever repeat himself. I listened to his criticisms as he went around the class. There were certain things that he said again and again, but there was always something new. Whereas Benton had a system which he could present to you, and he presented the same system to everybody. And then you did it or not.

PAUL CUMMINGS: How were they as personalities? I've heard about Benton a little but not about Robinson.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Well, Robinson was a more interesting man. He was like that in life, too; he was interested in lots of things. He would bring ideas from the outside to the class. Benton's style as a man was that there is a body of knowledge, and it is three feet long and three feet wide and one foot thick and that's it. He had also what James Truslow Adams calls the mocker pose. He liked to pretend. He liked to act as though he were completely uneducated and just the grandson of a crooked politician. I found that sort of tiresome.

PAUL CUMMINGS: He really is well educated though.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Oh, yes. But he's a little bit like that ancient joke about Gene Tunney and the book salesman. Gene Tunney these were you first studio classes then?

PAUL CUMMINGS: That's great. Well, lets see. At the League there were you first studio classes then?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes. They were life classes. They were drawing. Nobody taught painting there. You could paint if you wanted to, but they didn't know how to paint. There wasn't anybody in the League who knew how to paint. None of the teachers did. I don't think anybody in America knew how to paint in oils at that time. The Armory Show was a complete disaster to American art, because ti made people think that you'd got to do things in a certain style. They gave up what they did in order to do this new thing. It was a little like selling whiskey to the Indians.

PAUL CUMMINGS: It was a new thing for the Indians.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes. A few painters got something from it - got a lot from it. Marin got a lot from it. American art was provincial before, and it became more provincial as a result of the Armory Show. Of course, there were people who were... Provincial might mean dependent on somewhere else, or it might mean isolated form the world. In the latter sense, provincial meaning isolated from the rest of the world, there were certainly very good painters in America; but they weren't mainstream. Or they were dependent upon something else.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Yes. Who was in the Mainstream in the 1920s?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: France. Paris.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Oh, yes. But I mean in this country. Nobody?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Well, Marin accounts for himself; the people who Stieglitz showed, I guess; Benton. The mainstream in this country? I suppose Kenneth Hayes Miller in this country.

PAUL CUMMINGS: The American impressionists were almost...

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Well, people like Sloan and the illustrators of the American scene, who were naturally good painters, but then they... They had native talent , and they knew better than they thought. They didn't have any confidence or something. They couldn't keep on; they didn't know what to do next.

PAUL CUMMINGS: I was just thinking, you said that there wasn't anybody who painted at the League but that they all did drawings. I've just been looking at older American drawings and various things, and there seems to have been- through, well, from the Armory Show to even today - people who draw much better that they paint. They're still sort of afraid of painting or in awe of painting. They don't understand it or something. It's interesting that you, even in the 20s at the League, felt that.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I didn't feel it then. I thought they did know how to paint, but they didn't.

PAUL CUMMINGS: So Benton really didn't interest you as a painter then?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: No, not really.

PAUL CUMMINGS: How about Robinson's painting?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: No, he wasn't as a painter. He's a more interesting draftsman. I heard that Virgil Thomson once aid, I think in the 20s, that the center of intellectual live in Vienna is composers or musicians and in France it's the painters perhaps, I don't remember, and in America it's the journalists. That was in the 20s. So journalism was somehow the way that painters got a connection with the world. And cartoonists, for instance. The New Masses. The Masses. Radical journalism. Or else the American painters were expatriates or they were isolated, I think. I remember when Eakins died. I think he died about 1910, but he was completely isolated.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Well, Marin was to an extent, although...

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Oh, but he sold. He sold. He lived well.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Yes, but Dove certainly didn't live well.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: No.

PAUL CUMMINGS: He had a terrible time.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: But he had original ideas. They were just as original as any ideas in France. But that wasn't enough. You have to have more than that.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Yes. They have to go out and do things. They just can't stay home.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Well, he did things but they.... It was somehow an unnatural activity. There wasn't anything natural he could do about these ideas. I mean you couldn't do anything except isolate yourself further.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Well, I've often had the feeling about the painters of that period that the really modern ones - like the Stieglitz group as opposed to the newspaper illustrators and that whole Philadelphia crowd- were so distant from each other. The newspaper people - like Luks and Sloan and those people - were so involved in the sociology of the street and done in oil paints or something rather than painting problems and art situations.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Well, where it showed was in Bellows, who was a very, very talented person, and the journalists took him up. He was the favorite of the journalists. He wasn't an artist/journalist, but he was a journalist's artist. Then he began to read books about art theory and so on, and his painting just became no good at all. He applied theories of dynamic symmetry and of color and so on and so on instead of having a direct contact through his sensibility with the medium and with the picture.

PAUL CUMMINGS: They didn't believe in themselves, in other words. They always had to look elsewhere for reassurance and confidence.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Well, I suppose it's still because visually, at least in the arts, the country is still young.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Well, there were good painters in the nineteenth century.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Nineteen hundred was a funny year.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: It's very curious. When I see that picture of Manet's of the naval battle of the Civil War, which Manet observed and painted a picture of it... It's very hard to think of Manet as contemporary with the American Civil War; because his art is contemporary with the Harding administration or Coolidge.

PAUL CUMMINGS: That's marvelous. Well, I suppose it was at the League that you really started to meet other painters and get involved in the art world and the art scene in New York.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Who did you know there?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: The person I chiefly knew was Alec Haberstroh, who doesn't paint now. He makes props for a science fiction television program.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Oh, back to H. G. Wells. Was he a painter at the League?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: He was studying art at the League in the Benton class.

PAUL CUMMINGS: And he gave it up after a while?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Well, how about the older painters? Did you start to meet some of the older painters who were around then?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: No. I met Marin about 1938 or so. I met him in New York, as a matter of fact, at a friend's house. Oh, what was very influential was that I lived in New York on 15th Street. I had a room, when I first came to New York, in a rooming house. Once I left my room to go to the bathroom in the middle of the floor; and when I came back, a man came down from upstairs and introduced himself. He had seen a painting of mine in my room by Harold Weston. He knew Harold Weston and he invited me up to his apartment. He and his wife had a collection of Marin, O'Keefe, Dove, and so on and so on. They were friends of Stieglitz. So I met Marin there at their house, and I also met Paul Rosenfeld at their house, who influenced me very much.

PAUL CUMMINGS: In what way, would you say?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Well, as a critic. But his gift for language, his gift for language, his gift for being able to describe what something was like, to put it into words... When I wrote criticism, I was thinking of his criticism, not just of Berenson. I remember thinking of his criticism, not just of Berenson. I remember things that he would say. I remember telling him I didn't like Odilon Redon. And he said: What's the matter? Is he too ultra violet? And I thought that's exactly it! He had this impressionistic way of talking, which was extremely accurate, beautiful.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Well, you had an early interest in language it seems.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I guess so. I got that from my mother. My mother always had an interest in language, wrote very good letters.

PAUL CUMMINGS: When did you start writing then?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Not till after the war. I started writing art criticism.

PAUL CUMMINGS: In the later 40s?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes. I got into that from Elaine de Kooning who had been a reviewer in Art News. We went to a show at the Whitney Museum- a retrospective show of Gorky - and she talked to me about how good they were. I talked to her about how bad they were. We had a complete, thorough disagreement about them. Apparently I expressed myself so well that, when she was leaving Art News and Tom Hess asked her who could she recommend for a reviewer, she recommended me. I had just moved out here; and I sort of jumped at the chance because I had always thought that I would be good at this, better than anybody. I had always thought that, and they liked me right away at Art News. As a matter of fact, Frankfurter, who was the editor-in-chief then, said I was so intense he'd give me a year; but I stayed for about seven years. I could have kept on forever, partly because I as painting, which would give me new ideas. You see, if you're not painting and you're critic, you might get to an end and you'd have to repeat yourself. Or that could happen. At least I knew I got ideas all the time from what I was doing, which sort of renewed me.

PAUL CUMMINGS: So, as the painting developed, the criticism would change and develop?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes. And then I went around to artists' studios and looked at their work, because I was assigned to review something or other. The reason I was good was that I would try as much as possible, when looking at something that I had to review, to cease to exist myself and simply identify with this so that I could say something about it. But that wasn't simply my own idea. I learned that because I was told to do that (not in those words) by my editors. I remember once writing a review, and I was given a criticism by Frankfurter that I shouldn't sort of go like this all the time. He said what you should do is just report. Frankfurter said that the best criticism is simple the best description, and I think that is true. It's like the first page of the New Yorker. There's no finger shaking there. They just tell you as accurately as possible about something; and when you've read it, you have a very good idea of what you think and what they think and what judgment they make by their putting it definitely.

PAUL CUMMINGS: By their manner of description, because there are many ways of describing a thing.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I know, but accuracy is weapon, too. Sometimes this wasn't an unfriendly weapon either, because I have gotten letters from painter who said: What you say is true, and I've never seen it so well expressed before. Things like that. And de Kooning once told me... I wrote for The Nation for a couple of years after Art News, and the first thing I wrote was a criticism of de Kooning's show in 1959. Afterwards he told people - and he told me, too - that was the best thing that had ever been written about him.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Lets' see now. We've jumped way ahead. The Art Students' League... You must have left there about 1930, 1931.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes; 1930.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Well, how did the [stock market] crash affect you, the beginnings of the Depression?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Well, my father still was able to support me. I didn't have any financial problem until jut before the war. My father died, and things weren't doing so well. Then I thought I'd have to get a job somewhere, so I studied mechanical drawing and got a job. As a matter of fact, that was what I did during the war, because I was working for an industrial designer who was working for the Navy. They didn't want me to be drafted, so they kept telling the Navy that what I was doing was important. So I stayed on there throughout the war; and as soon as VJ Day came, I quit like that! I did have a little more money then, too. Then I studied with Jacques Maroger at the Parsons School. I learned a great deal from him. He was an art restorer. His background was that he had been head of the technical laboratory at the Louvre Museum.

PAUL CUMMINGS: That's right. He invented that Maroger Medium.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes, which I use now. And I also met somebody else then. In 1939 I was copying a Tiepolo at the metropolitan Museum, I was using the Maroger Medium; and a little man with very, very bad breath came up and spoke to me and said: You have light in your pictures. I don't know what I said about that. Then he said: I have never copied. And I said: Really? But I thought Renoir copied and so on. I mentioned all the Impressionist painters. He said: No, none, of them copied. I knew them all. Than he went away with his wife. He came back the next day, and I said: Oh, I'm very glad to see you. I thought here's somebody who knew all the great Impressionist painter. He said: Really? Sort of surprised. Then I got to know him. He was a painter named Van Hooton. He came around to the house with his wife. He gave me some lessons, a few, about three, in which he told me what I needed to have told me. I already knew it in a way, but I needed to have somebody say it - certain things about painting.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Who was he?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I don't know. He went back to France; he didn't like it here. He hated it here. He had fled from German Army to Vichy, France; from there to Tangiers; from there to Florida. He's been here five years, hated every minute of it, he and his wife. They went back as soon as they could.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Well, how did you get involved with Maroger?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Friends of mine, Edward Laning chiefly, were studying with him. And Reginald Marsh. I had a feeling that I didn't know how to paint, and I didn't know what to do. I mean, I had never learned it. It was very difficult. They said: Oh, he knows how to paint. He tells you the way that it used to be done. Then, when I did study with him, he showed me this Medium. It seemed to be so easy, natural that I stayed with it only for that reason; because it made things simple.

PAUL CUMMINGS: And you still use that?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes. Sometimes I don't. All of these pictures here use it. Sometimes I don't. If I don't use it, the fact that I have studied it somehow help me in painting just ordinary with turpentine. I don't know what it is, but something comes through so that the ease that I get from that passes over when I don't use it.

PAUL CUMMINGS: That' interesting. I talked to John Koch and he uses it. He kept saying it's so easy. He said he can change a whole area without having a big disaster.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes. You just move the paint.

PAUL CUMMINGS: That's fascinating. I didn't know that Maroger taught at Parsons.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: He did for a while. He taught mostly in Baltimore. But what I got from him was just the Medium. He didn't interest me otherwise, because he talked about the history of art. He measure everything by what he called the Medium. If you spoke of Goya, he would say: Well, he didn't have the Medium. And that was all he'd have to say about Goya. The last person he was interested in was Fragonard, because he did have the Medium.

PAUL CUMMINGS: I see. Well, what about Van Hooton? What did he say to you that was so important?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I could tell you, but it wouldn't sound interesting; because it's something that you have to do in paint. I mean, he showed it to me in relation to something I was doing.

PAUL CUMMINGS: You mean the manipulation of paint with...?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: No. Partly that; partly how to see it. I got things like that from de Kooning, too. If I told you the remarks that he made about a particular painting that I haven't got here and it isn't in the process of being made, it would sound banal. It's only banal when it's separated from what you're doing.

PAUL CUMMINGS: I see what you mean. So it's really an in-the-works kind of commentary that he provided.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes. He might say, for instance, that tree up there, that apple tree or the middle apple tree, he would say: That's not the shadow for the grass. I know he means when says that. If you just hear that remark, you might thinks it's not it's not the right shape or you might think all kinds of things. He would mean something about it's not in where it's supposed to be. The reason it's not in where it's supposed to be is because you haven't yet found the right color and thickness of paint and all kinds of things like that. It's It's like somebody criticizing a college theme and saying you haven't found the right noun in the sentence or the right verb. You're using adjectives because you haven't found yet the right words. If you find the right words, you won't have to ind these adjectives.

PAUL CUMMINGS: I see what you mean. We're leap-frogging in two different ways here. After you left the League what did you do?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I went to Europe; that was in 1932. I painted in new York, and I went to Europe in 1932. I came back and I got married. I have five children. And I just kept on painting.

PAUL CUMMINGS: And you lived in New York?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I lived in New York and outside New York near Croton, near Peekskill. When my grandmother died, we moved to Illinois to her house right next to my parents' house for a couple of years. Then my father died and we moved back East again. And very soon the war came. I didn't have any gallery then. I showed occasionally in group shows at the Art Institute, or at the Philadelphia Academy once in a while, or with the Artists' Union in Chicago. I also got interested in radical politics. But what I was interested in was... I met in Illinois- in Chicago- some German Marxists who weren't Communists. They were Marxists. They were more radical than Communists. They had never been Communists. They were associated with some American ex-IWWs, things like that. I was interested because of Hitler's advent to power. I thought this was too bad. I had been in Russia in 1927. I sort of read things- you know, what people said- and I noticed that the Trotskyites said there should be a united front with the Socialists. I thought obviously that is right, of course there should have been. I didn't like the way the Communists reasoned or rationalized. I thought I was a Trotskyite. Then I met these radical German Marxists and they showed me. They demonstrated. They didn't say, but I learned that Trotsky was just another Bolshevik and that the trouble was with Bolshevism, not Trotsky versus Stalin. It's Bolshevism that is the mistake, because of its method of organization .

The interesting thing about these Germans was that they had belonged to something in Germany called the Communist Workers Party, which was somewhat Rosa Luxembourg. I mean, she died before it was formed; so you can't say it was she but they were very concerned with... They thought it was very important that her criticisms or Trotsky's early criticisms of Bolshevism shouldn't come about; that is this becomes a centralized thing, one man dictates. So they were organized in a way that their enemies were never able to call them by a man's name with "ite" on the end of it, because they couldn't find anybody like that. They were organized in this way: Every year in Germany, the central committee of this party would sit in a different city in Germany; and it would be elected totally from the members in that city. One year the central committee was in Dresden, and it consisted entirely of the Dresden members. The next year it would be in Berlin, and it would consist entirely of the Berlin members. There was never any one bureaucracy or something that controlled it. So it was democratic. They thought that was essential.

They were very, very intelligent people. Paul Mattick was sort of a leading personality, and there were other Germans who were just as clever as he- and some Americans, too. What I got from them, from him was that they were sort of anti-theory. I mean, what you do comes first; and there isn't a theory which you then put into practice. You are what you are right now.

PAUL CUMMINGS: While you're doing it.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes. Which also, I like to think, is a common American way of thinking - that action comes before theory. Or it's a common Anglo-Saxon way of thinking. It's like British empiricism a little bit, and it's like...

PAUL CUMMINGS: Theory is history. You said you went to Russia in 1927. What prompted that?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: It was just curiosity. I was abroad with my brother, Edward; and we were walking around in France. Eliot had just gotten married and was on his honeymoon, and we met him in Paris. Once I wasn't with them, and they met a neighbor from across the street in Winnetka, Illinois, who was going to Russia with a group of American journalists, economists, and labor leaders. They were in a bad way; they needed some money. My brother said that I would like to go to Russia. He said, well, I think that can be arranged if he'd give us some money. So I went along with them. One fo the people was the Superintendent of the Winnetka Public Schools, a progressive superintendent. That was after my time. I was 20 at the time.

PAUL CUMMINGS: How did you find Russia then?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Oh, I thought it would be fascinating and it was. What I expected was I couldn't go to a place - not even China- that would be queerer or more interesting to see. That was what it was like. It was just absolutely... Everything was upside down; it was sort of different. Moscow, for instance, was a big city then; and everybody in the streets looked as though they had just come in from milking the cows. They didn't look like city people. The city was like a sea with big swells which had frozen. Red square looked like a great big wave of pavement. It was shabby and junky. There were a lot of wooden houses outside. We flew in by plane, and you looked down and there didn't seem to be any roads anywhere. There just seemed to be worn places where grass didn't grow, which were roads, I guess, and little trees, all second growth. AS you came down and approached Moscow, there didn't seem to be any reason for there being a city there. It was as though you'd find a city in the middle of the Northwest Territory or the woods or something. Nothing led up to it.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Yes, but it's on a river.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes, a little river; but when you came down, it didn't look that way. I mean you came into the city; and there were glass houses on the way in from the airport to the city, completely glass with bulbous domes. I said: what are those? They looked like greenhouses. They said: Oh, those are former summer houses of the nobility. It looked like Coney Island. The church on Red Square, you know the famous church, was like something in Coney Island. Everything is different. The church is very small, and it was painted on the inside like the decoration in candy boxes of about 1912. The walls were greasy from people's overcoats pressing against them. And this monument lifted from Coney Island...

PAUL CUMMINGS: That's extraordinary. How long were you in Russia?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Five weeks.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Where did you go besides Moscow?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: To Leningrad for a few days and to the Crimea, which is very beautiful and not so strange. I men, that is somehow related to Italy. We stayed in a sanitarium, which was supposed to be a sanitarium for incipient tuberculosis; but there were a lot of people who were there just because it was a nice place to spend a vacation if you had some pull.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Well, what did you think of Leningrad?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: It was terribly shabby. The streets were all tar blocks, which I had never seen before except that my father had a tennis court once made of tar blocks, you know, cubes of wood tarred. The hotel was more modern, more Western than the hotel in Moscow; but there were little bullet holes in the plumbing and the pictures on the walls. I thought that was the Revolution. It just hadn't been repaired. Before the Revolution, the aristocrats used to entertain themselves by shooting in their hotel rooms. Russia was so strange that it seemed to me probably true.

PAUL CUMMINGS: It fit.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes, it fitted. It wasn't that Russia was strange because of the Revolution; Russia was just strange anyway.

PAUL CUMMINGS: That's extraordinary. You couldn't have met too many people in that length of time.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I met a few Russians. Arthur Fisher, who got me in... Most people got sick in Moscow. They got colitis because they hadn't been inoculated for typhoid or something. They were terribly sick. Arthur was very sick in Moscow. This group of people wrote a report afterwards; his field was to write about foreign concessions in Russia, He sent me around to interview American businessmen, and it was very difficult doing that. It took all day to find one address and get there in a droshky over these streets in Moscow paved with round stones as if from the beach. All the streets in Moscow and particularly Red Square was like a great big gravel beach. There I saw that Shchukin and Morosov collection of modern art. These great houses of rich merchants were all sort of askew like this. They were settling. Moscow isn't on Bedrock; and the earth moves, I guess, a little bit so everything gets out of whack.

PAUL CUMMINGS: So, if it rains, all the buildings sort or lean to one side or something. That's extraordinary. Well I tell you, it's almost one o'clock.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Well, let's go.

MACHINE TURNED OFF

PAUL CUMMINGS: Now we're starting again here. You did a little teaching. You said the first teaching was for the Socialist Party in 1936.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes. Rebel Arts, I think, was the Socialist Club in imitation of the John Reid Club. I taught drawing to a class of amateurs, and then I became one of the editors of Arise which had four issues. It was a Socialist imitation of The New Masses. The other editors were Alex Haberstrill [Alec Haberstroh?], whom I've already spoken of; Sam Friedman, who was a real Socialist, an active, full time Socialist; Gertrude Weil Kline, who was also an active, full-time Socialist, a colomnist on the then New Leader, I think, which wasn't a bi-weekly but came out more often; and John Wheelwright from Boston. I wrote one article for them about mural paintings. I called it "Murals for Workers," which seems to me now like a very pretentious name. I wrote about murals that had been made mostly by the WPA or some of them not, because I included Thomas Benton and Orozco. I met at an editorial meeting John Wheelwright in New York and invited him to come out to Croton where we lived. He was interested in my wife's poetry and my ideas. I mean, we liked to discuss our ideas. I think he was sympathetic with Trotskyites who had joined the Socialist Party, and I was sympathetic with them, too. I was never an official member of the Socialist Party. I made a mural myself for a branch- Alex Haberstrill [Alec Haberstroh?] got me this for the Queens' branch of the Socialist Party- the subject of which was turn imperialist war into civil war, which also now seems to be very pretentious. It was in imitation of Orozco more or less, and I illustrated some of Wheelwrights poems for a time [‘Poems for a Dime'] which he published with linoleum cuts. I knew him quite well. We moved to Chicago when my second son was born and my grandmother died. Soon after that, he was killed in an automobile accident, but I always was interested in pets. My wife was a poet when I married her. She still is, but she doesn't write much now. Wheelwright's poetry I had read and admired before I met him. I think it's because I am somewhat in awe of any written of poetry. That continues after the war when I got in connection with the Tibor de Nagy Gallery who published O'Hara, Ashbery, Schuyler, and Kenneth Koch. I met them through the Tibor de Nagy Gallery, which I got into by Larry Rivers' and Jane Freilicher's and Bill de Kooning's and Elaine de Kooning's recommendations. After I had been writing for Art News for a few months, I wrote an interesting review of the Tibor de Nagy Gallery's first shows. When I saw their shows, I thought this is the place I would like to be in, and that was the place I did get into. I got just exactly what I wanted.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Great. You mentioned that, in 1936 when you were involved with the Socialist group, you started writing?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: The first thing I wrote was for Arise magazine, which was art criticism.

PAUL CUMMINGS: And that interested you into writing more and more?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I didn't write any more after that; that was the end of that. But when we moved to Chicago, we still had somewhat of a connection with the Socialist Party. Soon it was more of a connection with this group of Council Communists group with Matik and so on. But my wife in Chicago was asked to write something for May 1 in celebration of the anarchists, and she just by tour de force wrote something that could be sung. I remember Anne showing it to Wheelwright and Wheelwright saying: Of course, it's a tour de force. It's not very good, but I couldn't do it.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Well, you knew a lot of people involved with Socialist politics and so on.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes, but they were obscure people, the people I knew best. I liked them. I got to know these Germans; because when Hitler came to power, I used to see the advertisements for little publications; and I wanted to know what was going on. I wanted to see every point of view, and one thing would advertise another. Though their publication in which they announced a meeting, I met Paul Matik and Fritz Hentzler and Walter Auerbach. Those were the Germans whom I knew best; and there were some Americans - Givens I think his background was IWW and Bereiter, a German-American. His background was maybe something like that.

PAUL CUMMINGS: What was it about these.....?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: They seemed to me to be more intelligent; their ideas seemed to be better than anybody else's. That was why I was interested in them. Then I found out that they were among the few people in the world who had really read Marx all the way through, not just a little bit of it. At the same time, they weren't interested in measuring every opinion against Marx. As Matik once said - and this again seemed to be very intelligent of them - when somebody said to him: You're a good scholar, and you ought to stick to that. You don't know anything about practical affairs. This was a union man in Chicago at one of the meetings. His answer to that was: I don't care what Marx said; I'm only interested in action. It seemed to me that he was saying, too, that what is valid bout Marx is not that he is an authority but that it is scientific, and what is scientific is a description of the world. And a description of the world isn't to be measured by a book; it's to be measured by the world. I couldn't agree more.

PAUL CUMMINGS: How long did this interest in the Socialist group maintain itself?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I realized I never was good at reading Marx because I read too slowly. I liked these people because they were bright, clever; and they seemed to me to be... Well, they just knew more than American liberals or American Communists, who were also a form of American liberals I guess. I suppose it's a kind of dilettantism on my part; but still, if you're going to be interested in things out of curiosity, there's no point in taking second best.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Yes, that's true. Well, was this your first active...?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I wasn't really very active.

PAUL CUMMINGS: ...interest in politics?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Have you always maintained this interest in politics?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I used to read, because my family got The New Republic and The Nation. I read what they said about the Spanish Civil War and I'd read these other things. I realized that what they were saying referred to things that came out in other publications and that disagreed with them. So it showed that these things were not untrue, were not made up; but they suppressed them. So I felt... Well, this liberal point of view or the Communist point of view about the Spanish Civil War is not true. It's an edited one. It's a censored one. Walter Auerbach himself said that his interest in the radical movement in Germany after the First World War... I mention this because his interest came about in a similar way to mine. After he got out of , I suppose secondary school, he just stayed at home and read. He was interests in radical politics, and his brother said: Well then, you should go to the Communist Party. They're the people that put that into practice. So he went to a Communist meeting. They were denouncing the Trotskyites, and he didn't know who the Trotskyites were. He just knew that some people were being denounced. He said he'd like to hear what they have to say, and he was denounced. So he thought that was not for him. Then he found the Trotskyites weren't for him either.

Oh, I know what I wanted to say. What impressed me most deeply about this group of Germans was not just that they were more intelligent or that they knew more than anybody else but their manner of discussion was something that I had never met with before. If anybody said anything at one of those meetings, they were never interrupted even if they talked for three hours. People just sat and listened until the person had said everything that he had to say before somebody else got up to speak. There was no interruption. There was no bullying. I admired that very much. I never had seen that, and I don't see it now much either.

PAUL CUMMINGS: It doesn't happen much now. While you were in Chicago then in 1939, you had your first one-man exhibition?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes. That was sort of arranged by my mother. That was a family thing. She thought I wasn't enough known. She was pushing her son. She used the facilities at hand and got me an exhibition at the Winnetka Community House.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Do you remember what went into that show?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I only remember one picture which went into that show which I still have. It's a terrible picture; except it has one part in it that's nice and that's my son Lawrence my second son as a baby sitting in his mothers lap. I still like the way he's painted. The other pictures, I think, I've destroyed; and form that one, I think of cutting out maybe the bit of Lawrence and saving it.

Oh, this leads on to something else. The part in that painting I liked very much was the baby, my second son Lawrence. Later on when we moved back to New York, we kept seeing the Auerbachs, who lived in Philadelphia. We didn't see the other members of the group so much. Well, I used to paint pictures of Lawrence. I would say to Walter or to anybody: I don't think this picture looks much like him; He looks like his mother and this doesn't have that. Walter said to me one day: It's very interesting that when you paint pictures of Lawrence which you say look like him you bring out his resemblance to yourself, and when you paint pictures of him that you say don't look like him you bring out his resemblance to Anne. I thought that I thought just the opposite.

PAUL CUMMINGS: That's funny. Well, maybe it's hard to see. But about seeing all the paintings out of the studio and on exhibition...

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Oh I'm sort of ashamed of them.

PAUL CUMMINGS: It didn't do anything for you at that time?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Well, it made me see what a lousy painter I was, I guess.

PAUL CUMMINGS: It wasn't really an enthusiastic response.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: No. I mean, people were very polite and interested; and even quite a good Chicago painter expressed real interest in it. But that was like an older person seeing ability on somebody younger. I think that was all. That isn't what I was interested in. I was interested in performance, not promise.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Have you done any other teaching besides this one drawing class you had?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Yes. I taught at Southampton College a couple of years ago. That was pretty meager experience, too.

PAUL CUMMINGS: In what way?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Only a few signed up and fewer came. They weren't really interested. I had to sort of sell them the idea that this is worth doing, and I'm not interested in selling. If they're not interested already, I don't want to do anything about it. But then I've been invited to be a visiting critic quite often at art departments all over the country, and that's always very successful. It interests me and interests them. I have a good time, but that's at most a few day' thing.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Where have you done that?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Alabama, the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee, Oregon University, Kent State University in Ohio, Yale, the New York Studio School, the Maryland Institute, the University of Pennsylvania, Cornell.

PAUL CUMMINGS: You go there usually for a week or something?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Often just for one day. Alabama I went for a week, and I've been for several days at the Maryland Institute. I usually go to the Maryland Institute every year. They ask me back, I've been to the University of Pennsylvania several time and to Yale twice or three times. Yale has been my worst experience. Once I went down there and I was supposed to speak and I didn't write anything down. This was the second time I went to Yale. The first time it was all right. It took me a long time to get going; I didn't quite know how to talk then, The second time I didn't prepare anything. I thought it would be better to be spontaneous. I go very relaxed; and when it came time to talk, I had absolutely nothing to say. So since then, I've prepared something very carefully, written it out, and then read it. And that's what worked. ...also Skowhegan in Maine and an artists' association in Rockport, Maine.

PAUL CUMMINGS: What do you do?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I either give a lecture on some subject or other... At Kent State University, they gave me a subject. I like it when they do that. Then I can contradict the subject. The subject at Kent State was "The Arts Today - the Symptom of a Sick Society?" That was sort of fun; you know, that set you off. There were other people: an architect, Stockhausen, the composer, Agnes de Mille, and other people. They all talked before I did, so that gave me more and more things to say. You know it's always easier to talk second or third. And then, sometimes I've written those things up and given them as an article to Art News afterwards.

PAUL CUMMINGS: You don't criticize students' work?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I criticize students' work, yes. In these cases, I usually criticize students' work, too. There's a lecture, and then there's a couple of days... Sometimes it's just a lecture. Even if it's just a lecture, just one day, I'm taken to the students' studio for a couple of hours.

PAUL CUMMINGS: What do you find in the studios? Things that interest you?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Oh, I think they're mostly very good. The thing is that students are often very, very good; but once they graduate, there' a drop. There's a falling off. I don't know why that is. It's a different environment. They don't know what it's for. I found that to be true in cases where I didn't criticize. For instance, when Albers was head of the art department at Yale, the Museum of Modern Art showed students' work from Yale or just graduated from Yale; and they were very good. Then two years later you didn't hear from them again. Maybe they need this environment where there's somebody over them to encourage them or to whom their work is addressed. Then I've gone back to places and seen the same students the next year, and there's sometimes a falling off. They're just repeating themselves. If they really repeated themselves, actually you would be able to say the same thing; but usually the repetition of themselves also leads to a diminishing of the first thing. They don't quite live up to it, to themselves.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Well, how about the New York Studio School? That's somewhat of a different kind of school.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Well, yes; it's very informal. It isn't so different, say, from Skowhegan, which is very lively. Of course, Skowhegan gets the pick of art students from art schools from all over the country in the summertime. They were good, but they weren't any better than students in other places. One thing that I did notice about them was that they were more figurative than the general run of art students or the majority. As you get farther away from New York, the more they are like abstract expressionism, the more abstract they are, the more nonrepresentational they are.

PAUL CUMMINGS: It takes a long time for things to travel west.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Maybe so. They school of Hofmann seems to have percolated into the remotest corners of the United States.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Well, he taught for a long time, and there were lots of students, many very, very famous ones.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: Well certainly, judging by his students, he was the best teacher who ever lived.

PAUL CUMMINGS: You didn't study with him?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: No.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Did you know him ever?

FAIRFIELD PORTER: I've met him, yes. I'd heard about him first when I was studying with Benton. He came over to this country then; he was just out of Germany. Benton had written something in Arts magazine called "The Mechanics of Form Organization." Benton said that he had heard that Hofmann had said: Oh, that' very good, those articles of Benton; he has used all my ideas. Benton as very annoyed by that; he never had even heard of Hofmann. That's kind of Germanic, I think, to trace everything back to one source.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Yes, that's very funny, very dissimilar people. Let's see, what else was going on in the 30s? Actually then the war started to come along.

FAIRFIELD PORTER: In 1939, yes. That's when we went to the Pacific Coast- my wife and I and one of these Germans and his American girl friend. He was a very interesting person. He had been a lawyer in Germany and also a radical, and he knew German law and the way things were organized in Germany very, very well. I remember his being quite scornful of the fact that, during the war, he was assigned by the United States Government to teach Americans, who would be in the Army of Occupation in Germany, to teach the Germans democracy. He said that what these people were supposed to present t the Germans as an example of democracy was the government of the city of Milwaukee, which, as fritz pointed out, was copied from the government of German Socialist cities. They were just getting it back. There was a certain naiveté there.

PAUL CUMMINGS: Who was this fellow?